Richard and Joan Foxwist

- Date of Brass:

- 1500

- Place:

- Llanbeblig

- County:

- Country:

- Wales

- Number:

- I

- Style:

Description

May 2012

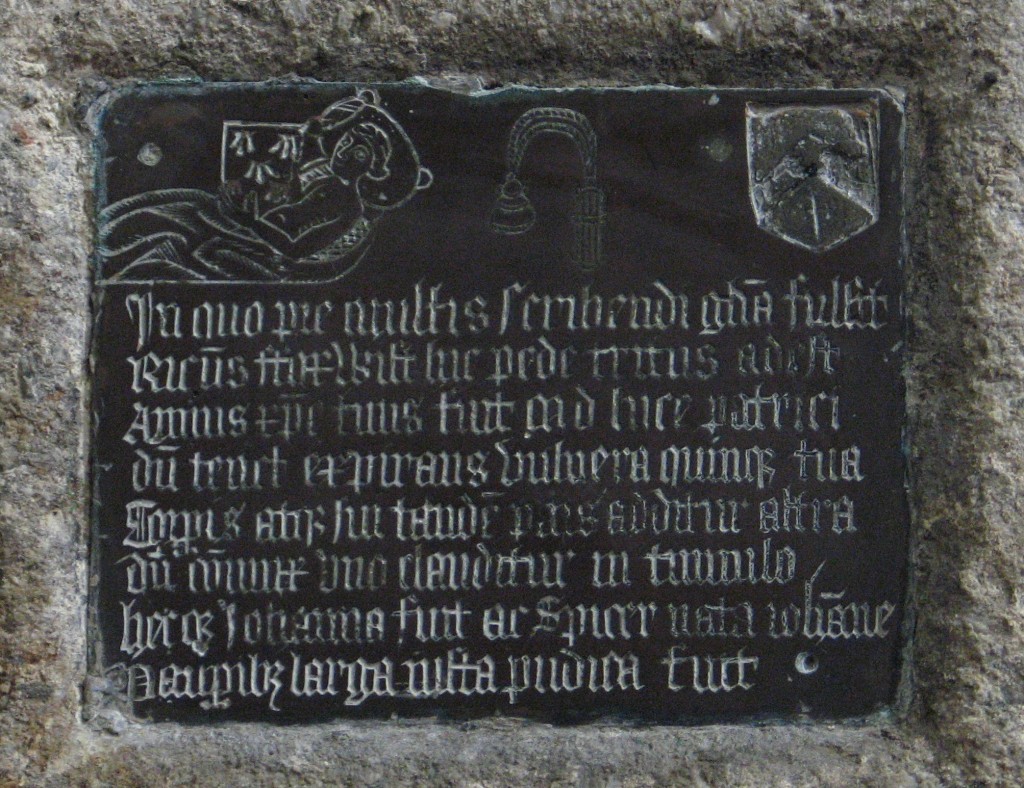

Medieval memorial brasses are surprisingly rare in Wales: J. M. Lewis lists seven before 1550, plus one from St Davids which has been lost, a couple of indents and a few brass letters. This is fewer than many English parishes. Those that survive are mostly typical products of the London workshops. There are some idiosyncratic ones, though. Sally Badham has said that one of these, the memorial to Richard and Joan Foxwist in Llanbeblig (the old parish church of Caernarfon), is like nothing else she has ever seen. She suggested that it might have been carved by a local craftsman who was clearly capable but more used to carving stone.

The brass panel depicts Richard Foxwist on his death-bed, propped up on a pillow, naked apart from a nightcap but covered with a blanket. In his hands (as the inscription on the brass says), he holds a little shield emblazoned with the device of the Five Wounds of Christ. To the right are the pen-holder and inkhorn of his trade as a scrivener, and his family coat of arms.

Devotion to Christ’s wounds was one of the most popular forms of late medieval piety and was particularly appropriate for a deathbed. In representations of the Last Judgement, Christ was depicted showing his wounds and surrounded by angels carrying the Instruments of the Passion. This was to inspire not guilt and terror but hope: the wounds guaranteed salvation.

While shroud and cadaver brasses are quite common in England, depiction of the actual deathbed is (as far as I know) unique. The closest parallels are with depictions of the seventh of the sacraments, Extreme Unction, and deathbed scenes from the popular medieval woodcuts accompanying advice on the good death, the Ars Moriendi. It seems likely that Richard and Joan’s children wanted a fashionable memorial for their parents, but had no standard examples to draw on and no contacts to order a brass from one of the London workshops. They thus came up with this unique design.

The other feature which makes the Foxwist brass so significant for our understanding of sixteenth-century Wales is the inscription. In floridly Renaissance Latin, it praises Richard as a scrivener, notes his devotion to the Five Wounds of Christ, and pays tribute to the virtues of the wife who survived him:

In quo pre multis scribendi gloria fulsit

Ricardus Foxwist hic pede tritus adest

Annus Christe tuus fuit Md luce patrici

dum tent expirans vulnera quinque tua

Corporis atque sui tandem pars additur altra

dum coniunx uno clauditur in tumulo

Hec que Johanna fuit ac Spicer nata Johanne

Pauperibus larga iusta pudica fuit

(Richard Foxwist, in whom the glory of writing outshone many, is here trodden by foot. Thy year, O Christ, was 1500 in the Father’s light when he expiring holds Thy five wounds. And at last the other part of his body is added when his wife is enclosed with him in one tomb. She, who was Joanna, daughter of John Spicer, was generous to the poor, just and modest.)

However, almost unique among memorial inscriptions of the period, it makes no mention of prayer for their souls. Virtually all medieval memorials included a request for prayer (usually in the form Orate pro anima ... ‘pray for the soul of ...’) or a plea for God’s mercy (cuius anime propicietur / miseretur deus, ‘on whose soul may God have mercy’). Indeed, much of the incentive for the construction of elaborate memorials was the encouragement they provided for prayer for the souls of those commemorated. The Foxwist memorial, by contrast, reads like an early example of the Renaissance cult of fame.

We cannot be sure of the date of the brass. Richard Foxwist died in 1500, his wife tandem, some time after, and the brass was presumably commissioned by their children. The issue of the validity of prayer for the souls of the dead was to become one of the flashpoints of the sixteenth-century Reformation. Wales was slow to respond to most of the changes of the Reformation, but here in one of the little towns in the north-west we may have an echo of the new thinking. There is nothing else radical about the memorial. It is entirely conventional in its iconographical focus on the wounds of Christ as the route to salvation. The Foxwists were clearly not committed reformers, but their memorial does have elements of the thinking of the reformers. Taken with the neo-classical Latin of the inscription and the very idiosyncratic design, it looks as though we have an aspirational family with some new ideas. These may owe more to fashion than to spiritual commitment, but fashion is important in providing a constituency for changing attitudes.

- © Monumental Brass Society (MBS) 2024

- Registered Charity No. 214336